Edmunds' GraphQL Federation Adoption (Part 2)

Yuhan Zhang, Suresh Narasimhan

In Part 1 of this article, we talked about our motivation for adopting GraphQL Federation and how we restructured our existing REST apps into subgraphs to connect to a supergraph with GraphQL Federation. Individual teams owned the subgraphs, and as the number of subgraphs grew, GraphQL deployment became critical. As teams created and evolved their subgraphs we wanted the GraphQL deployment infrastructure to catch compatibility, performance issues and enforce standards.

At Edmunds, our apps go through canary deployments with spinnaker. This worked well for us, and we wanted to check if we could do the same for GraphQL.

In part 2, the discussion will focus on how we fit our GraphQL apps into our existing continuous delivery pipeline with canary deployment and how the supergraph app is set up to protect against backward incompatible changes from developers or poorly designed queries. We will also discuss strategies to improve the schema and optimize performance.

GraphQL Deployment

Our proof-of-concept GraphQL subgraphs were deployed along with our REST apps/microservices. After completing the proof-of-concept, the subgraphs were deployed as standalone artifacts. The main challenges with GraphQL deployment were:

-

Super Graph Composability: If a new version of a subgraph is incompatible with the other subgraphs, the federation server cannot compose a supergraph, and the federation server will fail to start.

-

Backward Compatibility to Clients: A new version of a subgraph may be compatible with other subgraphs to compose a supergraph, but it can still be incompatible with the live queries on production. Or, the new supergraph may be incompatible with the client. For example:

- Removal of a required field, changing the return type of a required field and changing the type of a required parameter.

Although using Apollo Studio solved the two issues above, we couldn’t achieve canary deployments with Apollo Studio. As a result, our app was deployed with a fixed schema and didn’t have a schema registry to poll and apply schema. A schema registry is a single point of failure. It also risks deploying an incompatible schema to the live environment if the schema check is imperfect. The Netflix GraphQL article had a similar opinion and mentioned “[their] gateway dynamically [updated] its schema by polling the schema registry. [they were] in the process of decoupling these by storing the federation config in a versioned S3 bucket, making the gateway resilient to schema registry failures”. By chance we did not get into using a schema registry. On the other hand, it meant that we were required to reload the supergraph after a new version of subgraph was deployed. We were able to avoid reloading of schema by using canary deployment. (Our canary deployment performed a gradual transition of both supergraph and subgraph.)

SuperGraph Composability

Being unable to construct a supergraph would cause a major failure in production. Thus, it is important to test out the schema construction offline. This can be done by running a supergraph offline with a new version of a subgraph offline, to compose with the other subgraphs in production. Then we can verify if the new version of a service starts and composes a supergraph.

Schema Compatibility Check

After the new version of a subgraph is able to compose, we need to know if the new supergraph has a schema change. The schema change must be compatible with all the live queries in production and returns results in the same types so that the new schema does not break the client.

A naive approach would be to replay logs at the supergraph. This option is implausible when your traffic is large. Replaying can only cover a sample of limited cases, and replaying itself costs resources and takes a long time. Instead, it is desirable to find the field usages of the live queries with the current supergraph, and compare it with the field usages of the live queries with the new supergraph. This requires the following:

- The schema of the current supergraph in production

- The schema of the new supergraph in staging

- The queries in production

- A tool to find out the field usages given a schema and queries in production.

- Diff on the field usages of two schemas.

The schema can be easily obtained at your supergraph by npx get-graphql-schema http://localhost:3000/graphql/ (likewise for production).

The queries in production can be collected through your log. By default the GraphQL federation was performing HTTP POST for queries, which is hard to trace to the query in the access log. HTTP POST did not make sense as our application involves mostly reading. So, instead of HTTP POST, we configured our Apollo Client’s fetchOption to perform HTTP GET at GraphQL supergraph. (See the below section GraphQL Persisted Query for details.) Apollo Gateway is already capable of handling HTTP GET out of the box. This allows the query and variables to appear in the URI path with &query= and &variables=. Consequently the queries showed up in the log. Since the URI path can be very long with a GraphQL query, the load balancer needs to be adjusted to allow larger header size. To shorten the urls, we enabled GraphQL persisted query in the client. (See below in GraphQL Persisted Query for details) The persisted query feature also helps us collect queries from logs like we do with other REST apps.

We developed an in-house tool to estimate the GraphQL field usage. Given a schema and a query, the tool will parse the query with the graphql-tag library, a dependency of the NodeJS GraphQL implementation. The tool traverses the selection in the parsed query’s OperationDefinitions. Each field usage is output in one line, in the format of {type_name}.{field_name}:{value_type}. For a parameter usage at a resolver, it is written as {type_name}.{field_name}@{parameter_name}:{value_type}

For example:

- Inventory.mileage:Int is a field called mileage in our Inventory type and it is an integer.

- EditorialSegment.segmentRatings@pagesize:Int is a parameter called pagesize as an integer value, on the resolver of EditorialSegment.segmentRatings.

With the query field usages stored to a file, a diff can be easily made to find out the incompatibility in two different schemas. This tool currently handles usages in read operations of fragments, parameters, enum, and interface. (We have a plan to opensource this tool.)

With the query log and field usage, it enables us to make a detailed report at how GraphQL serves the data in our website:

- GraphQL schema for a given date

- A list of field usage in one GraphQL query

- A list of field usage over all GraphQL queries

- Refer page with the field usage

- Versions of subgraphs at each deployment

- Field added / removed at each deployment

This report is used as a guide in case we need to manually roll back in an emergency.

The compatibility validation is webhooked with our gitlab merge request process, , along with resolver complexity setting for further protection. The validation fails a bad merge request before it can be even checked in.

Reflect the new supergraph

Once the two validations above pass, the new supergraph is ready to be applied. As mentioned earlier, at Edmunds we didn’t start with Apollo Studio and we found a schema-registry module unnecessary. The setup in the basic example works well itself. That saved us from the burden of maintaining such a service. In exchange, our supergraph needs to be reloaded when a subgraph is deployed.

Getting the new schema can be easily done by calling apolloGateway.load() after the new subgraph is in place, and then you can assign the loaded schema and executor to a running apolloServer.

const { schema, executor } = await apolloGateway.load();

const schemaDerivedData = await apolloServer.generateSchemaDerivedData(schema);

apolloServer.schema = schema;

apolloServer.schemaDerivedData = schemaDerivedData;

apolloServer.config.schema = schema;

apolloServer.config.executor = executor;

apolloServer.requestOptions.executor = executor;

We placed the logic in the server and exposed it to an HTTP endpoint. Since the supergraph schema is stored in the memory of every server, It requires calling the endpoint at every instance in the cluster. This is not as automatic as the polling mechanism with a schema registry, but gives more control at loading the schema of supergraph.

Meanwhile, actively calling schema reload could also be error-prone. Notice that there is a flaw in this approach: a new instance of the server may start up any time by autoscaling. A newly started server may apply the new version of the subgraph to compose a supergraph. That means with this setup, there is no guarantee of serving with a certain version of the supergraph schema. To really address this issue, the new version of a subgraph must be isolated to its designated supergraph cluster from its stable version during the deployment. (We no longer follow this unreliable approach of reloading schema and have proceeded with canary deployment.)

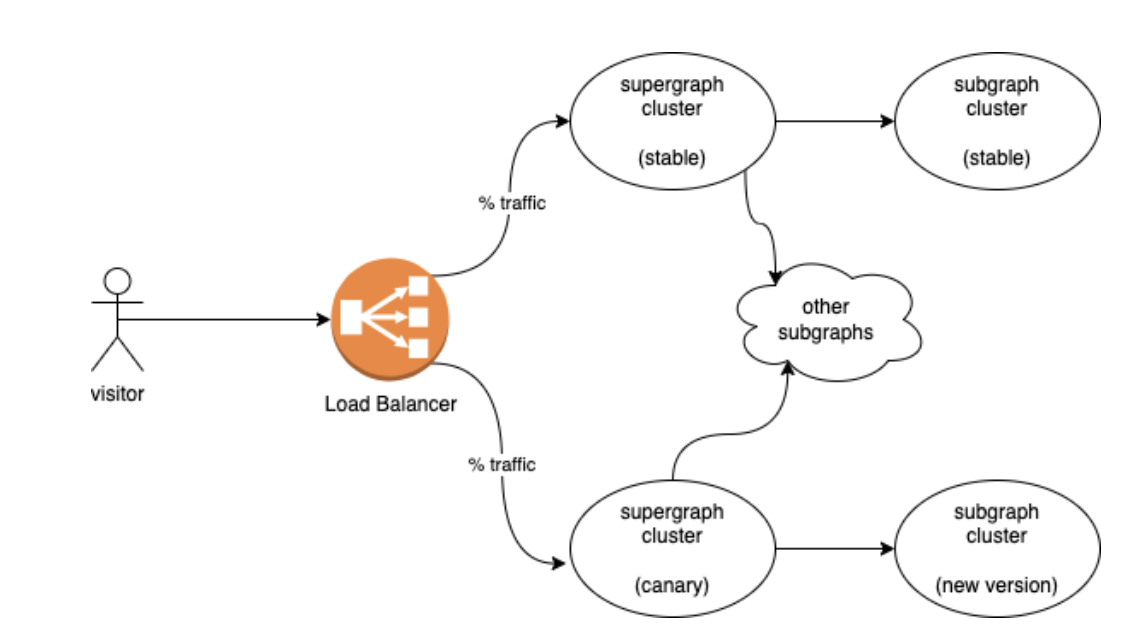

GraphQL: Canary Deployment

To make canary deployment happen, a new version of a subgraph and a new supergraph cluster (of the same version) are tied as a pair during deployment. A true canary deployment not only gradually applies traffic to the new version of the subgraph, but also gradually applies traffic to the service with the new supergraph schema. Since two supergraphs are isolated, starting a new supergraph instance is not an issue, and we can avoid reloading the supergraph schema on the fly all together.

Performance, error log and HTTP status are then measured using our existing CD-pipeline to gradually switch the traffic. (We modified the HTTP status on errors. See below.) The new version of a subgraph is launched with the supergraph cluster once traffic is switched completely. If the new version underperforms, both the canary supergraph cluster and the new version of subgraph will be trashed and traffic will be switched back to the stable supergraph.

Enforce a Standard for Operation Concerns

HTTP GET vs. HTTP POST

By default, ApolloGateway will use POST calls to communicate to each subgraph. Typically, GraphQL errors are included in the response body and response status can still be HTTP 200 despite an error. This does not fit our existing monitoring and alert setup, which largely depends on HTTP error status. Using HTTP GET also takes advantage of CDN cache. Our internal REST cache uses the url path as a cache key, following the convention of a CDN. Our canary deployment pipeline checks HTTP status to decide if a test passes.

Luckily, the ApolloGateway endpoint can accept both POST calls and HTTP GET calls, taking &query= for the GraphQL query, &variable= for variable replacement. Making the Java subgraphs to read HTTP GET is as easy as changing the annotation from springframework @POST to @GET, and from requestBody to @QueryParam. To make ApolloGateway call a subgraph using HTTP GET, we implemented our own subclass of RemoteGraphQLDataSource, which performs HTTP GET. The custom DataSource is provided as part of buildService.

class HttpGetGraphqlDataSource extends RemoteGraphQLDataSource

{ … }

new ApolloGateway({ buildService: ({ name, url}) =>

new HttpGetGraphqlDataSource(

Object.assign({ name, url }))

})

To override the HTTP status of GraphQL, we defined our own plugins , which overrode the behavior during requestDidStart , where request headers could be read from requestContext.request.http.headers.get(..), response headers could be set in the return value of as willSendResponse with requestContext.response.http.headers,set(..) . The HTTP status can be assigned in requestContext.response.http.status. Having content in requestContext.response.errors results HTTP 400. To make an HTTP 500 error, we throw an error in our .willSendResponse method. The plugin is also a good place to collect StatsD metrics, set tracing HTTP headers, override logger, implement custom validation rules, and forward HTTP headers and proxy HTTP status from / to the subgraphs.

GraphQL Persisted Query

GraphQL queries are usually large. Moreover, since GraphQL with HTTP GET keeps the GraphQL query in the query parameter, GraphQL query cannot take the advantage of the compression in Content-Encoding. Fortunately, ApolloGateway provides Persisted Query, which can represent a query with a Hash. Persisted Queries are defined on the fly (not predefined) - convert a query to query hash and query with the query hash; if the query hash cannot be resolved, make a second call with both of the query hash and the query. This protocol has been implemented to Apollo-Client in JavaScript, and made transparent to the developer - developer can just treat it as if it is querying directly with the GraphQL query. To enable Persisted Query, add a persisted query link during initialization of an ApolloClient.

import { createPersistedQueryLink } from '@apollo/client/link/persisted-queries';

new ApolloClient({

link: ApolloLink.from([new RetryLink(...), createPersistedQueryLink({ sha256 }), new HttpLink(…)]),

…

});

To perform HTTP GET with persisted query, configure the fetchOption in HttpLink to use HTTP GET:

const fetchOptions = {

timeout: 700,

method: 'GET',

};

On the server side for ApolloGateway, enable the persistedQuery option along with the plugins options. Since we have multiple instances of ApolloGateway, we chose Redis as a shared cache to store the persisted queries.

const { RedisCache } = require('apollo-server-cache-redis');

…

persistedQueries: {

ttl: 3600,

cache: new RedisCache( redisHost )

},

To force frontend developers to use only persisted query, a validation has been set up in the GraphQL plugin to check for the &extensions= parameter. The validation will cause HTTP 403, failing any usage of Graphql without the Apollo-Client. This was a great feature to fail QA canary deployment for frontend developers who didn’t follow the standard. Since the validation happened only on HTTP GET calls, tools like GraphiQL and Voyager still worked the way they were through POST calls. However, later we found out that in a retried GraphQL query, the url was always provided without the persisted query hash. Thus, this enforcement feature was only enabled in the QA environment and never on production.

The benefit of Persisted Query is not limited to the bandwidth saving. It also helps us define a limited number of queries, and use &variables= well to prevent proliferation of queries. This further opens us to tracking and automated deployment.

GraphQL Complexity

GraphQL provides the flexibility for developers to make their own queries, but we still want to prevent a developer from doing crazy things. This can be done by limiting the complexity of a query in the supergraph. At each GraphQL subgraph, we measured response time metric at the Resolvers (aka DataFetchers in java-) by iterating them from graphql.schema.idl.RuntimeWiring and wrap each DataFetcher into a subclass DataFetcher to plot the milliseconds that a resolver takes, sending as Statsd metrics. By summing up for a total cost of the query, we have an estimation in the worst case on how slow a GraphQL query may respond. The total cost is used as the complexity of a query. If the complexity is greater than a predefined max complexity value, the query needs to fail. The following options are added to the GraphQL options.validationRules:

- graphql-cost-analysis for limiting the maximum complexity

- graphql-depth-limit to limit depth of nested queries.

The complexity plugins cause a bad query to fail in canary deployment, preventing infeasible queries to be released in production.

Accessibility

GraphiQL Explorer made it easy for developers to click and choose fields to select. It improves the productivity of the team to make ad hoc queries, or just to study the data. Displaying the supergraph schema GraphQL Voyager makes your API more understandable.

GraphQL Optimization

Caching

Since our GraphQL traffic had been modified to act through HTTP GET, it easily took the advantage of CDN cache and our internal API Gateway cache. Our API cache follows a convention to use Cache-Control value to direct a cache purge. Forwarding of the Cache-Control header allows to trigger a cache purge from the supergraph to all the subgraphs related to a query.

Compression

We enabled compression at the express.js app on the ApolloGateway. Also, passing Accept-Encoding: gzipin the HTTP request header through the plugin calling the subgraphs helps saving bandwidth in the response.

DataLoader: GraphQL Java vs. NodeJS

It is common to fetch the child entities of entities in GraphQL. If implemented uncarefully, it would result in a fanout of many calls from resolvers. It is better to group calls into a batch call. For this purpose, DataLoader is provided by both the NodeJS implementation and the Java implementation. The NodeJS DataLoader is automatic but depends on the process.nextTick function . It works with fetching entities of entities, but often suffers from fanout when entities nesting level increases. The Java DataLoader on the other hand, provides developers more control.

Choose a Good Query Root

Besides the accommodation with DataLoader, undesirable fanout in resolvers often suggests a problem in schema design. It is tempting to design the GraphQL schema to be a tree from the most abstract to the most detailed types. However, it would mean unnecessary fetching of the abstract entities in every query, just to provide a filter point. It is more practical to start the query root with an entity type having higher cardinality - having more properties to filter on, and let the abstract types to be the properties.

In our case, a root query with vehicle modelYear is a lot easier to query by providing parameters model_name and year, compared to querying a model entity at the root, and then querying modelYear entities in the next level by filtering by parameter on years.

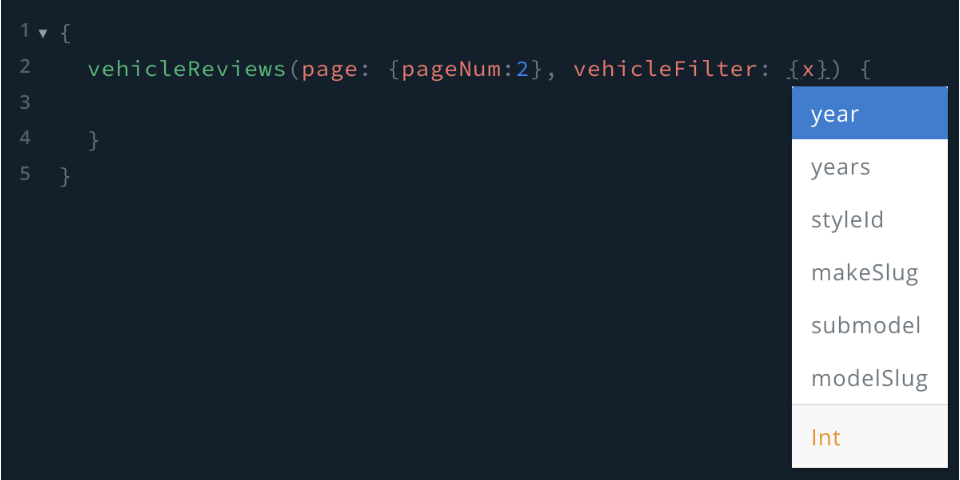

The downside of choosing a detailed type as a root query could be having too many parameters at one type. Thus, it is necessary to group parameters into complex Input types. For examples: pagination can wrap pageSize and pageNum; sortBy can wrap fields to sort on and sorting directions as value; vehicleFilter can be the parameters to filter by vehicle model and year; reviewFilter can be parameters to filter by rating score and topic. Having complex Input types becomes self-explanatory and is easy to navigate in GraphiQL Explorer.

Improving Schema Design

The point of having GraphQL Federation is to query mixed subgraphs. The ApolloGateway (the federation server) doesn’t contain any Schema. All graphs are defined by the subgraph. Thus, to join two subgraphs, a type in the other subgraph is redefined with @extends annotation, and with @key to identify a way to get the object from the other subgraph. On the other hand, subgraphs do not talk to each other directly to fetch entities. Through the @extends annotation, subgraphs lets the supergraph (federation server) decide how to perform a fetchEntities call to the original definition and perform a mixing.

- @extends: suggests there is an original type definition on the other subgraph. This subgraph adds fields.

- @key: suggests foreign keys to provide to the original type definition in the other subgraph to fetch entities. This subgraph should provides the foreign keys

- @external: suggests that the field came from the original type definition in the other subgraph.

- @requires: suggests to get a list of external fields from the original type definition in the other subgraph, before this resolver can do its job.

With GraphQL Federation, each subgraph can be a microservice without knowing other subgraphs, but can still enrich a type originally defined by other subgraphs. A page can be served completely by making exactly 1 query through the join of different subgraphs.

In Edmunds use case, vehicle data is our basic types, and other data such as consumer reviews about a vehicle model live in a different subgraph, but can extend vehicle type to include consumer reviews for a vehicle model.

Conclusion

GraphQL Federation is easily adoptable if your organization is already on microservice architecture, and it is highly customizable to meet the existing REST standard to work with infrastructure and tools built around REST. In Edmunds, 20% of our API calls go through GraphQL and are growing. GraphQL makes it easy for documentation, tracking, and flexibility, enforcing standards, and promoting good designs.

Yuhan Zhang is Tech Lead on the Service Engineering team at Edmunds.

Yuhan Zhang is Tech Lead on the Service Engineering team at Edmunds.

Suresh Narasimhan is Engineering Director on the Service Engineering team at Edmunds.

Suresh Narasimhan is Engineering Director on the Service Engineering team at Edmunds.

Do projects like this interest you? Edmunds is hiring: https://www.edmunds.com/careers/